|

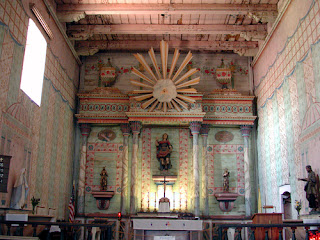

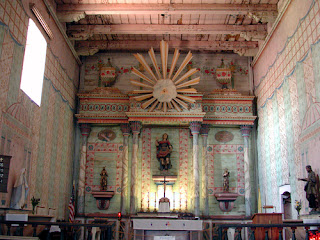

| Mission Carmel |

SACRAMENTO -- You may have noticed that I've not posted here much recently. I am in my summer hiatus mode, and I just returned to my native land of California to see family and friends. It is summer break time.

Recently, a few friends asked me about a piece I wrote in 2006 about the pilgrimage Lori and I undertook to all 21 of the Spanish missions in California. The missions were established by Father Junipero Serra in the 18th and 19th centuries, and every fourth grader in California learns about them.

The missions begin in San Diego, and are one day's horseback ride from each other along the El Camino Real stretching to Sonoma north of San Francisco Bay. We did not ride horses, but rented an RV. It took us two weeks to visit all of them.

Here, for your summer diversion, is the piece I wrote in 2006 for the Diocese of California about the missions:

+ + +

On the California Mission Trail

We started out on a rainy November evening, driving South in a rental motor home. We were headed to San Diego to begin a two-week pilgrimage to see all twenty-one California missions founded long ago by Spanish Franciscan padres.

We had no idea what we were getting into.

Our plan: Drive South, and then start working our way north, one mission at a time, camping along the way with our dog, Chulita. We started at the first of the missions, San Diego de Alcalá, founded in 1769 in a river valley that was once the exclusive domain of the Kumeyaay Indians and is now dominated by shopping malls and a giant sports stadium. Next, we drove a half-hour to Mission San Luis Rey de Francia in Oceanside. And onward we went for the next two weeks.

As we lumbered northward, on some days we managed to see three missions, even four, while other days we saw only one mission or took a break.

The day after Thanksgiving we pulled into Sonoma and the last of the missions, San Francisco Solano, now a state park. Along the way we experienced not only slices of history, but found amazing communities still living faithfully in the missions.

Why did we set forth on this pilgrimage? The short answer was to see the vestige of California’s past that I have heard about since 4th grade like every California school child. The more complicated answer was that Lori and I wanted to experience the places where Christianity first came to California. Yet this was not just an exercise in antiquity. We wanted to know: Could the past be transformed into something new that speaks to the era in which we live? Are the missions more than museums? And what unexpected wonders would the missions yield?

|

| Mission San Antonio de Padua |

We found powerful, holy places, each offering a unique spiritual oasis. The location seemed not to matter; some missions were tightly wedged into a city while others were down an isolated dirt road. Some missions were amazingly peaceful, like San Antonio de Padua. Others were spectacularly beautiful, like the ruins of Mission San Juan Capistrano in the sprawl of Southern California. And we found communities alive with faith. At San Luis Obispo we arrived at the noon Sunday mass. There were two baptisms that day, and the service alternated between English and Spanish. At Santa Inés, near Solvang, we arrived in time for a wedding.

The first nine of the missions were founded by Father Junípero Serra at San Diego; other Franciscans built more missions after his death at Mission San Carlos Borromeo del Rio Carmelo (Mission Carmel) in 1784. The twenty-one missions were strung from San Diego to Sonoma, each about a day’s horseback ride apart along El Camino Real, roughly following the route of what is now modern Highway 101. Several major California cities eventually formed around the missions: San Diego, Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, San Jose, and San Francisco. Others remained isolated and a few missions languished from the start.

Each mission was a working ranch producing food, cowhides and other products for sustenance and sale. The Franciscan vision was that each mission would be a self-sustaining monastery. While that vision is long dead, it is still possible to glimpse mission life as it once was. Mission La Purísima Concepción, near Lompoc, is in a state park that is preserved much as it was in the Spanish era. The only way to the mission is to walk down a dirt road, and La Purísima is still operated as a working farm.

An even more isolated mission, San Antonio de Padua, is on an Army base, Fort Hunter Liggett, nestled in the hills east of San Simeon. We had to drive past a tank and go through a security check point to get onto the base, and then drive another six miles to find the dirt road leading to the mission. The faithful from the surrounding countryside go through this routine every Sunday to go to church at Mission San Antonio.

The day we arrived, we had Mission San Antonio all to ourselves and we sat for a long while in the peaceful sanctuary. Above the altar is a wooden arch painted sky blue and adorned with gold stars. I found the light switch and when the lights came on it was as though the entire sky lit up.

Some of the missions today are little more than ruins, while others have only a small chapel on a site near the original mission. Yet each mission is a jewel. Every mission, we discovered, has been shaped and reshaped by grace-filled people for generations. All but two of the 21 missions are still functioning parishes, and the two that are not are nonetheless unmistakably holy.

|

| La Ofrenda at Mission San Juan Batista |

The missions range from the ornate to the simple. In every mission, we found the symbols of piety from two centuries in a wonderful holy mix. We found old Spanish mission art next to Indian wall paintings, and Mexican Day-of-the-Dead shrines near shrines to Spanish Franciscan monks. Outside, contemporary statues of St. Francis were near the bright orange, blue and yellow wall hangings of Our Lady of Guadalupe. Nestled in the gardens were 18th century niches devoted to St. Benedict near the graves of Indians and Spanish monks. Even the ruins bulged with bells and statues and beautiful fountains. Everywhere we went we found a feast of color, symbol and life. Seeing California one mission at a time gave me an incredible sense of how each California community is connected to the other. Instead of whizzing up and down I-5 at 75 mph, we stopped every 30 miles or so to see a mission and the community that surrounds it. I can't really say where Southern California ends and Central California begins. In all, we drove 1,550 miles of California back roads and highways.

There were many surprises along the way. Mission San Fernando Rey de España, on the northern edge of the Los Angeles Basin, is now a convent and also the burial place of comedian Bob Hope. The story goes that his wife, Dolores, asked him where he wanted to be buried. “Surprise me,” Hope replied. She did. His gravesite in the mission convent gardens looks like a miniature Hollywood Bowl.

Contradictions abound along the mission trail.

The missions were places of great pain. The Spanish padres who founded the missions used – and abused – the Indians in the surrounding regions in the name of Jesus Christ. The mission histories are difficult reading, documenting kidnappings, torture, and uprisings. Spanish soldiers forcefully rounded up Indians in the countryside, killing many. Tens-of-thousands of Indians died from European-born diseases, buried in mass graves near the missions. Today a few missions have memorials to the dead Indians, for example at San Juan Batista where a simple wooden sign marks the mass grave of an estimated 4,300 Indians buried on the grounds.

Yet as earnestly as the Franciscans tried to convert the Indians to European ways, the influence of the Indians on the missions is overwhelming to this day. The Spaniards are long gone, but the Indians are still there tending to the missions and their imprint is everywhere for those who have eyes to see and ears to hear. At Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, an Indian holy man showed school children the mission of his ancestors, and he played a musical instrument that his father taught him to play. In other missions, abalone shells, spiritually powerful objects for the Chumash Indians, hold Holy Water in wall niches. Shells decorate graves at Mission Carmel and shells adorn the tabernacle that holds the Sacrament at Mission Santa Bárbara. The walls and ceilings in many of the missions are painted in bright blues and oranges, reds and yellows in geometric patterns designed by Indians.

The California missions have a tumultuous history beyond the Spanish era. The Franciscans maintained that they were holding the mission lands in trust for the Indians, but in the 1830s the new Mexican government secularized the missions, essentially revoking land rights for Indians and the Church alike. Secularization affected each mission differently. The Indians in San Luis Rey were so distraught that their priest was leaving when the mission was secularized that they marched 30 miles to the San Diego harbor to plead with him not to return to Spain.

|

Artist Christian Jorgensen painted watercolors

of the mission ruins in the late 19th century |

Many of the missions were abandoned and fell into disrepair, ravaged by earthquakes, floods, fires and neglect. In 1848, the United States acquired California – and the missions – as spoils in the Mexican-American War. In the 1860s, Abraham Lincoln returned many of the missions to the Roman Catholic Church. But it was not until nearly a century later that the missions were rebuilt, many in the 1930s as WPA projects. Mission San José, in Fremont, is the last of the missions to be restored. A wooden Gothic-style Catholic church on the site was sold to the Episcopal Church for $1 and moved across the Bay to San Mateo. The old Spanish mission was reconstructed in 1985 and is spectacular.

A few missions barely exist today. Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad, out in the lettuce fields near Salinas, was washed away in a flood in the 1820s; all that remains is a small chapel and a few weather-worn adobe walls marking where the mission once stood. Yet the mission still has a congregation and a group of elderly Mexican American women eagerly showed us their mission.

The missions reflect the rich history of diversity in our state. Mission San Francisco de Asís (Mission Dolores) in the heart of San Francisco, has the graves not just of the Spanish monks but of Irish immigrants who came in the years following the Gold Rush. At Mission San Rafael Arcángel, Sunday Mass is offered not only in English and Spanish, but also in Haitian, Vietnamese and Portuguese. In the garden is a memorial for homeless people who have died on the streets.

Nearly all of the missions have shrines and votive candles devoted to those who have died. Lori made it her practice to light a candle everywhere we went.

At San Juan Batista, a special altar has been set up in a transept adorned with an American flag. People have placed on the altar photographs of men and women who are serving in the military, with notes asking for prayers for their protection and safe return. We lit candles and silently prayed before we left.

It struck me that despite the flaws of the Spanish missionaries, the Gospel still finds a way in these missions to break through to a hurting and broken world – and breaks through to this day. The padres who founded the missions had something in mind that ultimately did not succeed: they attempted to build New Spain and turn the Indians into Franciscan monks. Politics overwhelmed their project and disease and abuse killed most of the Indians. The missions, as originally conceived, failed. Yet the Spirit succeeded. The missions still are hugely sacred places, alive with the Spirit and alive with people. The faithful who tend the missions gave me hope that however flawed my own efforts are, the Gospel will still find a way.

|

| Mission San Miguel |

Mission San Miguel Arcángel is one such amazing place still proclaiming the Gospel despite the odds against it. Isolated on a lonely stretch of Highway 101 in a neighborhood of shacks and trailers, the old mission was badly damaged in an earthquake three days before Christmas 2003, and the sanctuary remains closed to visitors. The congregation holds Mass in a converted storeroom, sitting on metal folding chairs. An outdoor altar on top of an old mission millstone offers visitors a place to pray. Mission San Miguel has many cracks but it is still a holy and living place. The only thing holding up repair work is a lack of funding; the mission has more than enough volunteers.

[Note: Since this writing, Mission San Miguel reopened.]

Our journey ended in Sonoma, at Mission San Francisco Solano, built in 1823 as the northern most outpost of the Spanish-American Empire. The mission is now a state park and the chapel is no longer a functioning church. The interior suggests what the mission might have looked like. We walked the grounds, pausing outside at an old wooden wagon that had once hauled the harvest from the fields. A few blocks away is Trinity Episcopal Church, on East Spain Street, on what was once mission land.

At the end of our journey we celebrated at a nearby restaurant on the Sonoma Square, and we gave thanks for our safe passage and for this amazing land of California. And we would gladly do this pilgrimage again.

By James Richardson, Fiat Lux